I’m fortunate to be surrounded by people who want to do good in the world. “Civic tech” is – perhaps obviously – full of such people, but so is tech generally: many people building tech genuinely believe that their product helps improves people’s lives. And yes, the Todoist app does help me organize my to-dos more easily, and I have heard busy parents laud food delivery apps which take the major burden of meal management off of their plates.1

Then there is tech explicitly geared toward “social good”: these are usually companies that have a mission to reduce inequality or increase safety or security measures for a given community such as access to food or housing. These are companies that believe they can be sustainable in – which is code for derive profit from – the pursuit of helping society, usually vulnerable or typically underserved segments of society.

I’ve worked for such companies – back when phrases like “social entrepreneurship” were cool and even more recently – and participated in Code for America brigades filled with people who wanted to work at or start such companies. I’ve had to hold up the mirror and ask hard questions about myself and about what we were really doing:

Can you truly be motivated by what’s good for a community while being motivated by profit? Will profit always win out? Do you know enough about the problem to help build viable solutions? Can you truly achieve societal change without changing the system itself?

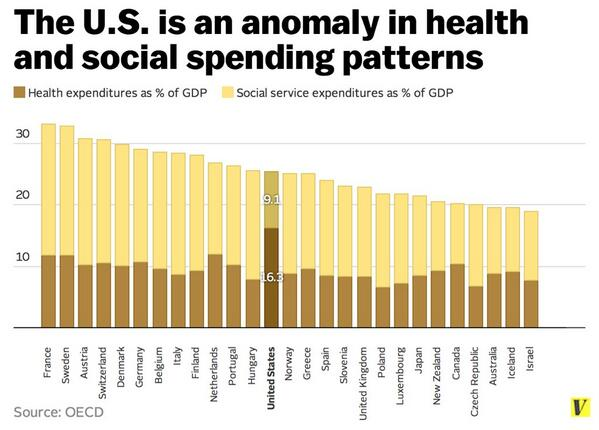

This latter question is a huge topic that usually boils down to the debate between gradualism versus revolution, which I don’t want to get into now. Check out Jessica McKenzie’s blog post for a great discussion on when civic tech can be bad, illustrated by different gradualist vs. revolutionary, for-profit and not-for-profit approaches to the US welfare system. Her concluding proposition is one that I think we should be using as a value measure for all civic or social good tech:

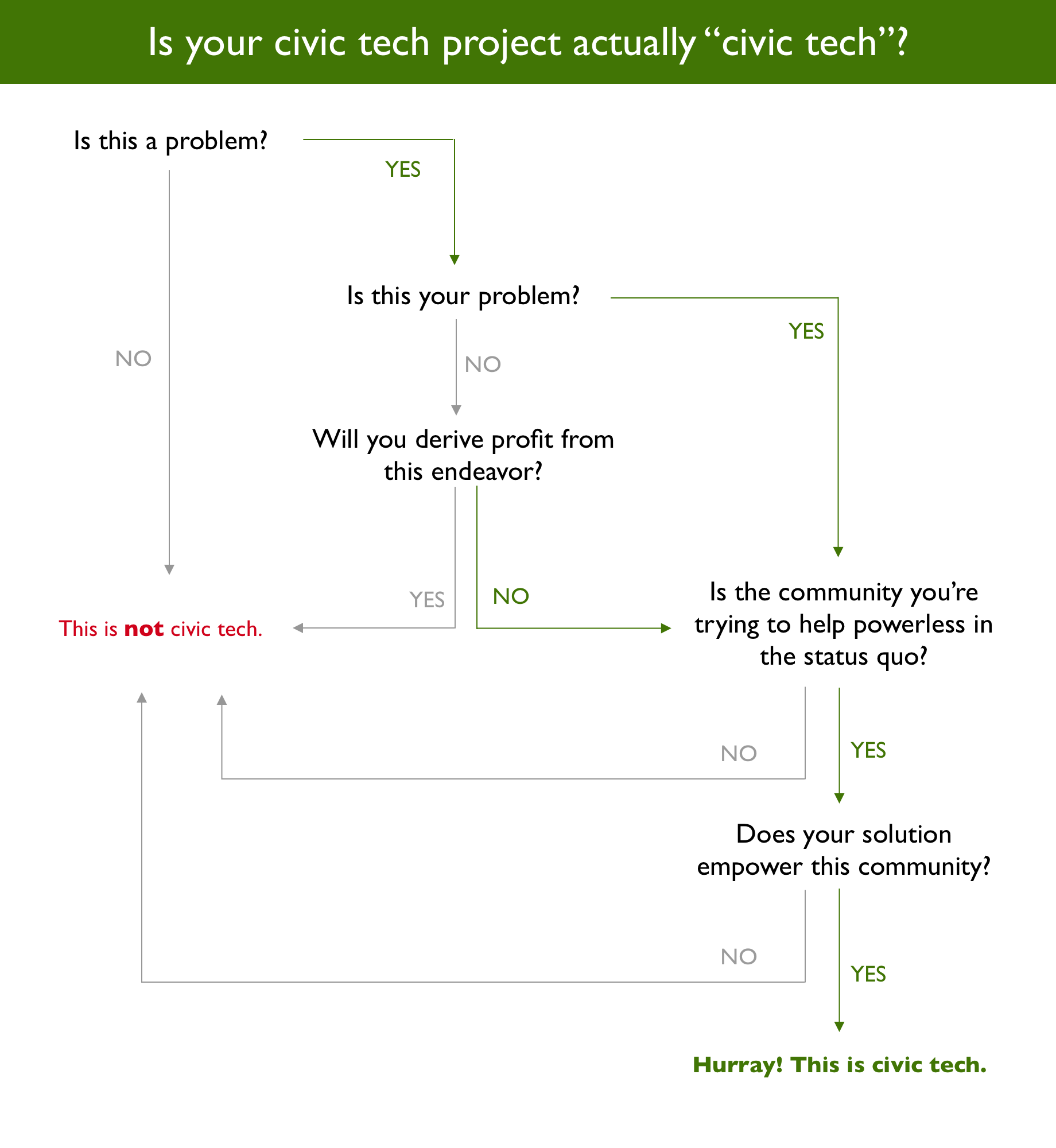

Civic tech should strive to empower the powerless—not as a byproduct, but as a foundational premise. If it shifts power away from the powerful, so much the better.2

So, how do we use this measure – how much did we empower the powerless and how much did we shift power from the powerful – when critiquing civic tech projects?3 How do we help people embarking on these projects, who are often from privileged backgrounds or do not have lived experience of the problems they want to tackle – use this as a guiding principle from the outset, before they ever lay hand to keyboard?

There’s some great writing on this topic, and in my opinion we really need more of a revolutionary approach to most problems. However, it may be the gradualist in me that recognizes that right now, people who want to do social good in the world are starting their own projects and often their own companies, and many of them won’t know how or want to tackle real systemic change.

The following are questions I’ve started to use to break this down for myself when I consider joining a civic tech endeavor, as well as for well-meaning people when we talk about their ideas to help others.

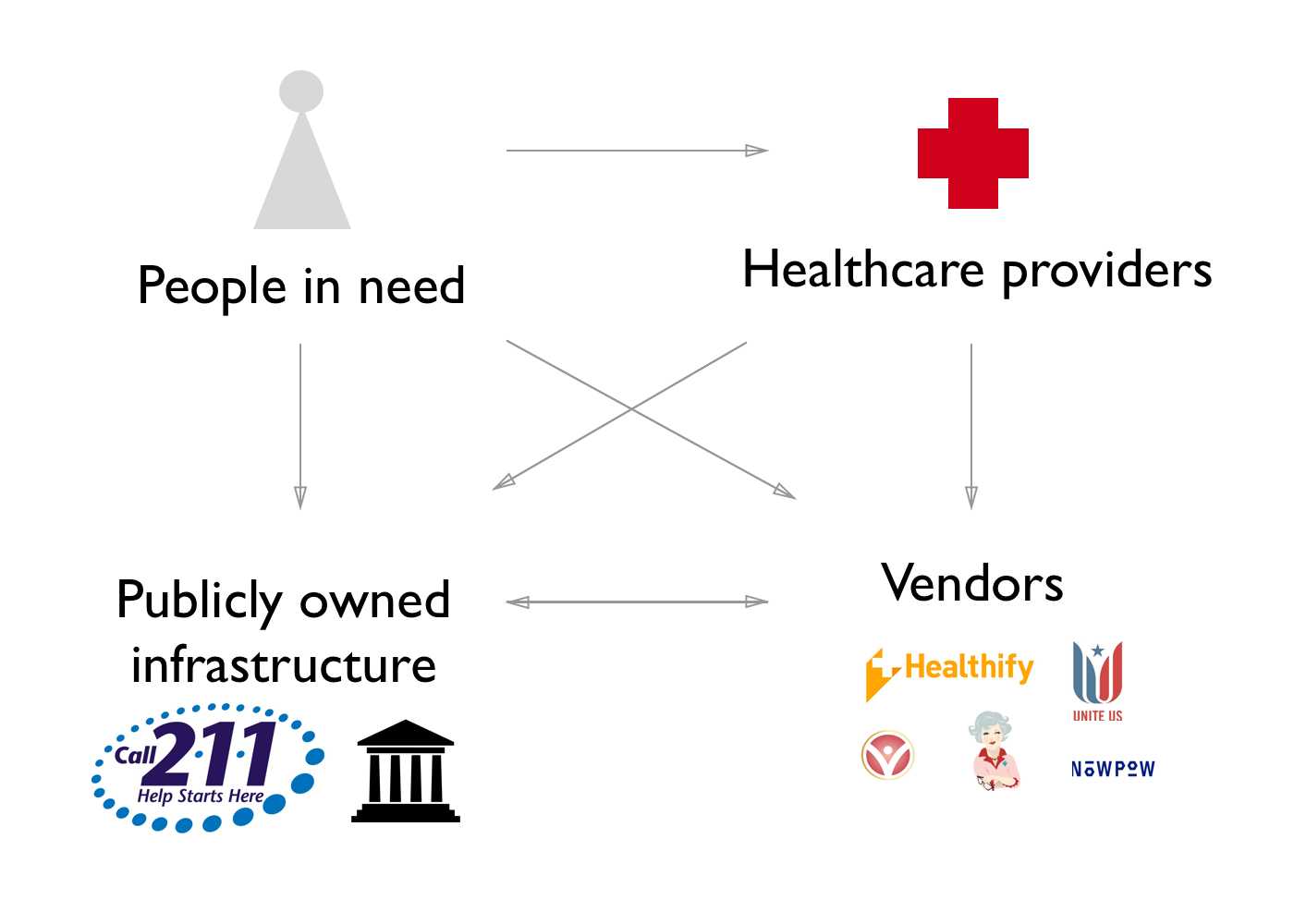

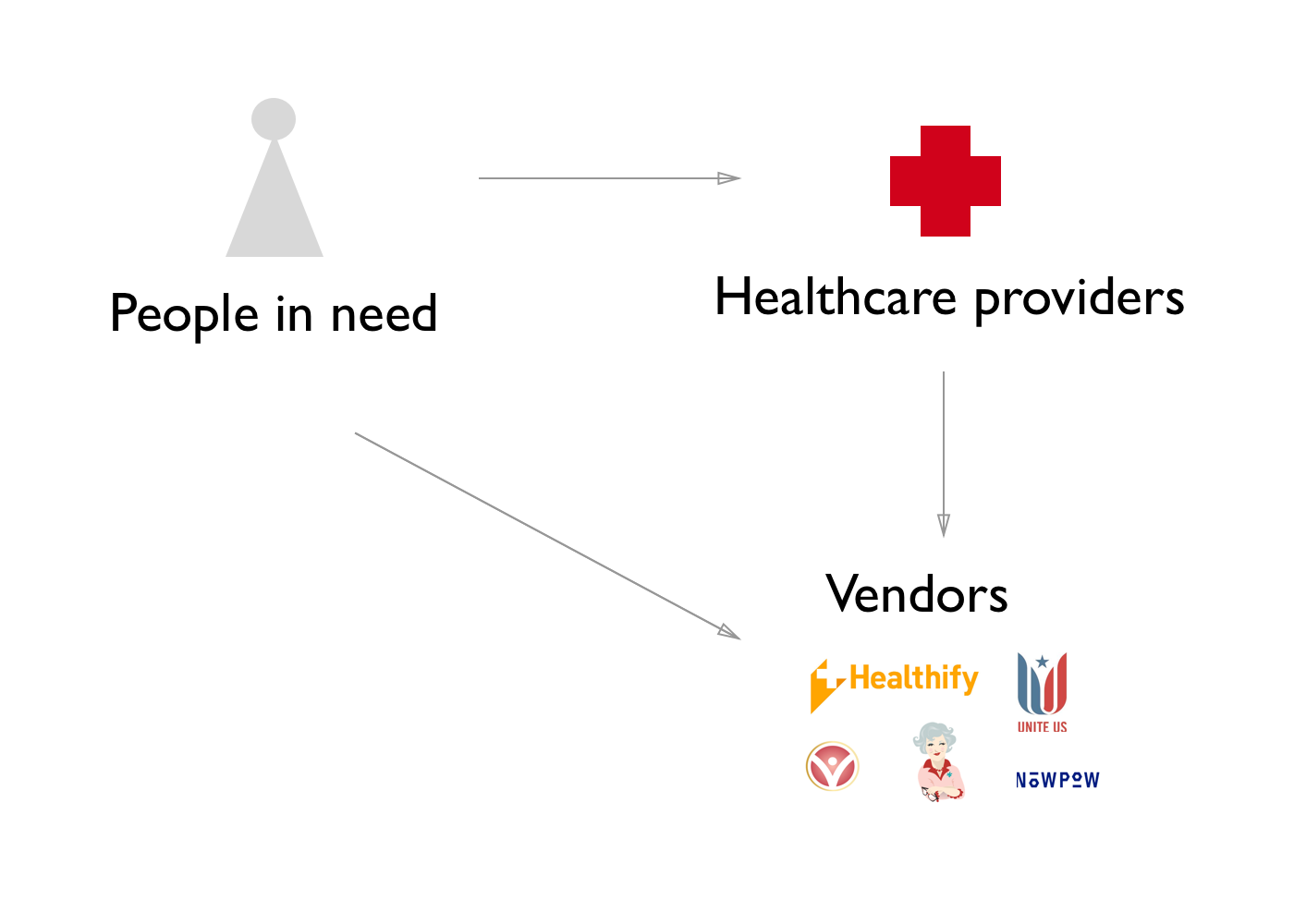

I’ve even attempted my first flowchart ever:4

1. Is this a problem?

Or is this a symptom of a bigger problem? Or neither? Is the problem that there is no way to apply for affordable housing online in your city, or is the problem that there is a 10 year waiting list for affordable housing for seniors, or that there simply aren’t enough affordable units? Or, that our approach to affordable housing needs more holistic reform to address systemic race and class oppression?

2. Is this your problem?

If you’re not part of the community you’re purportedly trying to help, stop and consider whether you’re suffering from the “white savior complex” (even if you’re not white). That’s not to say you can’t help, but if you’re in this situation, the most important thing you can do in your attempt to help is listen. The next most important thing to do is learn as much as possible about the status quo and how it got here, and keep an open mind.

This question extends not only to you personally but to your founding team. Does anyone in this team have meaningful, lived experience of the problem? It’s critical that the people who will hopefully benefit from your solution have a voice in the solution (through user feedback or being on the product team), and ideally, that they actually have a seat at the table.

3. Will you profit from this endeavor?

This is primarily relevant if the answer to #2 is No. Profit isn’t necessarily exclusive from civic tech, but it is if you are trying to profit from an already vulnerable community and will not share those profits with that community. For real change and empowerment, the community being served by the solution and driving any profit for the owners of solution should be the ones deriving that value and therefore that profit.5 When that’s not the case, it is literally exploitation.

4. Is the community you’re trying to help powerless in the status quo?

It’s very possible that you are part of the community you’re trying to help but that that community isn’t the one who needs help. For example, if you believe your problem is that the school board doesn’t know what parents want, and you want to build an app so that parents like you in your neighborhood can be more vocal to the school board, you should ask, who are these parents?6 Are they middle or upper class white folks? Do they already have outlets for voicing their opinions or exerting power and influence? If you believe this is an app for all parents, ask who would even be likely to use such an app and who might take up the most space on it. Are there parents in different neighborhoods or from different demographics who might be adversely affected by such a product? Would the parents in your neighborhood be vocal about policies that would hurt parents (and students) in another neighborhood, not out of malice but simply through lack of representation and space?

Ultimately, this means that you have to know who all the stakeholders are. You can’t look at a problem in a vacuum. You have to seek to understand why the status quo exists and who currently benefits from it – because someone always benefits.

5. Does your solution shift power to the powerless?

Once you understand the stakeholders and the factors at play, you can start to ask whether your solution or project idea will actually change the status quo, and whether it will change the status quo to empower the powerless. If it doesn’t, go back to the drawing board and the community you’re in, learn more about social work and grassroots activism, and be humble enough to recognize when you may not have a good solution. This is the hardest thing for me and I’m guessing for most people: you believe so much in your idea – and you want to help so much – that it’s hard to acknowledge when it won’t have the impact you want it to.

I’m not saying all this to be discouraging. We need more people caring about and thinking about these problems, and we need people with the energy, drive, and skills to help. But, we don’t need many new ideas.7 We don’t need people trying to solve problems on their own without deep thought and research about the problem and without hard consideration of their own biases. We don’t need tech people with buzz words, or people coming into cities telling civil servants that they need design thinking. We don’t need people riding in like knights in shiny user-centered armor.8

So, I hope these questions are helpful for anyone thinking about how they can get involved or start civic tech (or social good) projects. Listen, keep listening, and don’t profit from the vulnerable. Make your goal be changing the status quo to empower the powerless – whether in big or gradualistic ways – and keep measuring your impact by that as you go.