What do human rights, open standards, and venture capital have to do with public infrastructure?

Jan 25, 2019

What so much of the conversation around civic tech boils down to is the question of public/private partnerships. What is the role of companies, specifically tech companies, in our communities, and what is the role of government? And, assuming we will always have both,1 how should they work together for public good?

I’m not going to wax lyrical on all the many economic, poltiical, and moral facets of this question, but I did recently spend three years in a position that put me face to face with this question on a daily basis. This is some of what I’ve learned.

The tl;dr: Services that are necessary to protect and enable human rights, and the infrastructure to deliver those services, should be publicly owned.

The Three Sectors

Many of you reading this probably work in the private sector. “Private sector” is a fancy term that basically means for-profit companies. Just to make sure we’re all using the same lingo, there are three sectors:

- Public: These are organizations or institutions owned by the public. This sector often goes by the colloquial term “government.” I’m putting this one first because it’s the most important.

- Private: These are owned by private individuals or fang-toothed venture capital funds.2 While in the US people often use “private sector” to include privately held non-profits, I think it’s clearer to think of private as for-profit, and that’s how I’m going to use it in this post. If a for-profit company is publicly traded, technically members of the public can own it, but you must have the qualification of money, not humanity, to do so.

- Third: While I see this term mostly used outside of the US, I think it’s a good way of describing nonprofits or non-governmental organizations (NGOs).3 They’re the ones always taken for granted: they are supposed to be motivated by mission, not moolah,4 and I’ve heard self-described “libertarians” cite them as the people who will pick up the pieces of society out of philanthropic kindness in place of government. Indeed, in many places, they often already do this.

When I was young and bright-eyed and just getting into tech, I didn’t know much about the Three Sectors.5 After working at nonprofits and getting more involved in civic tech, I learned even more about it, especially the relationship between the public and third sectors. It wasn’t until the past few years that I experienced first-hand how the private sector does, can, and should play into this.

The productization of social services delivery

This case study is about social services with a focus on Healthify because I recently spent three intense, often very fulfilling years in that space with that company.6 However, in this section heading you could easily replace “social services” with any other public service or function of government, and you’ll probably be able to find examples of this happening in that area.

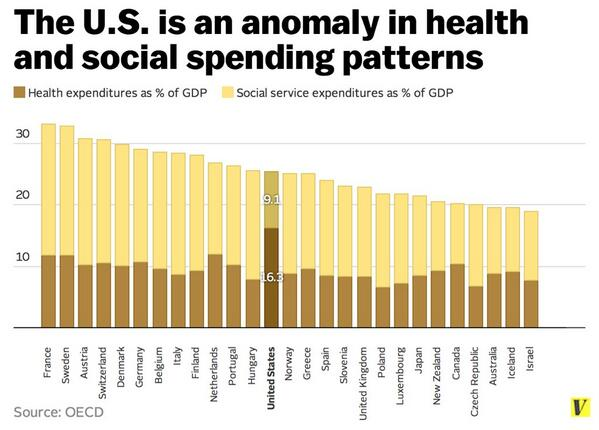

Healthify is a for-profit software and services company whose mission is to “build a world where no one’s health is hindered by their need.” They want to do this by building community health infrastructure (systems, technology, relationships) to connect underserved populations with the social services they need to thrive and ultimately improve health outcomes. Tangibly, their long-term goal is to flip the ratio of spending on healthcare vs social services in the US based on percentage of GDP.

As you can see, the US spends proportionally much more on healthcare than on social services, unlike comparable countries. Healthify believes that doing the opposite will reduce spending overall and produce better outcomes for people. They’re out to prove that and to make it happen.

There’s a lot that goes into this – including need identification and referral coordination software and client services that help health systems build networks with community-based organizations – but it all started with data. Data about social services.

The social services data

Healthify’s product started as a search database for social services. Most (if not all) of the other vendors out there have something similar. There are three notable things about this data:

This is local data. A single large national call center isn’t very useful in collecting and maintaining this data, because the people curating the data need to be well-versed in local issues. The housing issue and housing-related services in San Francisco, for example, are way different than their counterparts in Ann Arbor – and the data reflects that.

This is public data. You’re probably paying for the maintenance of this data in some way via tax-funded grants to 2-1-1s (more on them below) or nonprofits, and even if you’re not, you’re certainly paying for the actual upkeep of some of these services, and those services are the creators of the data in the first place.

This data is necessary to uphold human rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights decrees that

- “Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in [their] country” and

- “Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization…of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for [their] dignity and the free development of [their] personality.”7

I think we can all agree that for someone to be able to access public service and resources for their social security and realization of rights, they need to have basic information about those services and resources. This data is that very information.

But it’s not just about the data itself. It’s about making the data discoverable and accessible, by which I mean understandable and useable by all people. To do that, we need more than CSVs on a thumbdrive or a call center that verbally gives this information out on the phone. We need infrastructure.

The social services infrastructure landscape

This may sound somewhat familiar to you. If so, you may be thinking about 2-1-1, which is a nationally-reserved hotline for people seeking human and social services assistance. 2-1-1s may have a national brand, but they are all locally or regionally managed, with over 70% run or funded by UnitedWay.

Being decentralized and run by nonprofits, 2-1-1 is usually at least indirectly funded by taxpayers depending on local circumstances. They’re typically underfunded, and the quality of their services and data available to the public varies dramatically.

Six years ago, Healthify founders working in community clinics felt that neither 2-1-1 resources nor the physical binders being manually maintained by fellow community health workers were good enough, so they set out to create their own database that could do it better. This story is pretty similar to how other vendors, such as UniteUS, got into this space: through personal experience with outdated, nonexistent, or poorly performing public infrastructure.

Private (or third) sector innovation can start as a response to inadequate public infrastructure, and that’s okay.

Today, the landscape for human and social services data currently looks consists of these major players:

- 2-1-1s

- Other community nonprofits addressing social service delivery

- Vendors

- Google (or other search engines)

- Build-Your-Own by health systems seeking to address the social determinants of health

It’s pretty competitive, which in some ways is a good thing for social workers and their clients. The competition pushes actors to have better data and build useful, usable software on top of it. However, because there’s no real shared infrastructure, they’re all doing redundant work. The amount of human and machine data verification and improvement that goes into maintaining a good community resource database is immense, and every actor here is doing it in a silo.

Furthermore, because this data is necessary to uphold human rights, then the infrastructure supporting its delivery is also necessary to uphld human rights. This means that we can’t just rely on private actors, and ideally not on third sector actors either. Private actors shouldn’t be able to decide who gets access to this data and how. The people who produce or rely on the data – in other words, all of us – should own the data and its infrastructure; ergo, there needs to be a publicly owned actor.

Possible versions of the world

All of this can play out in different scenarios. I’ll illustrate three of them:

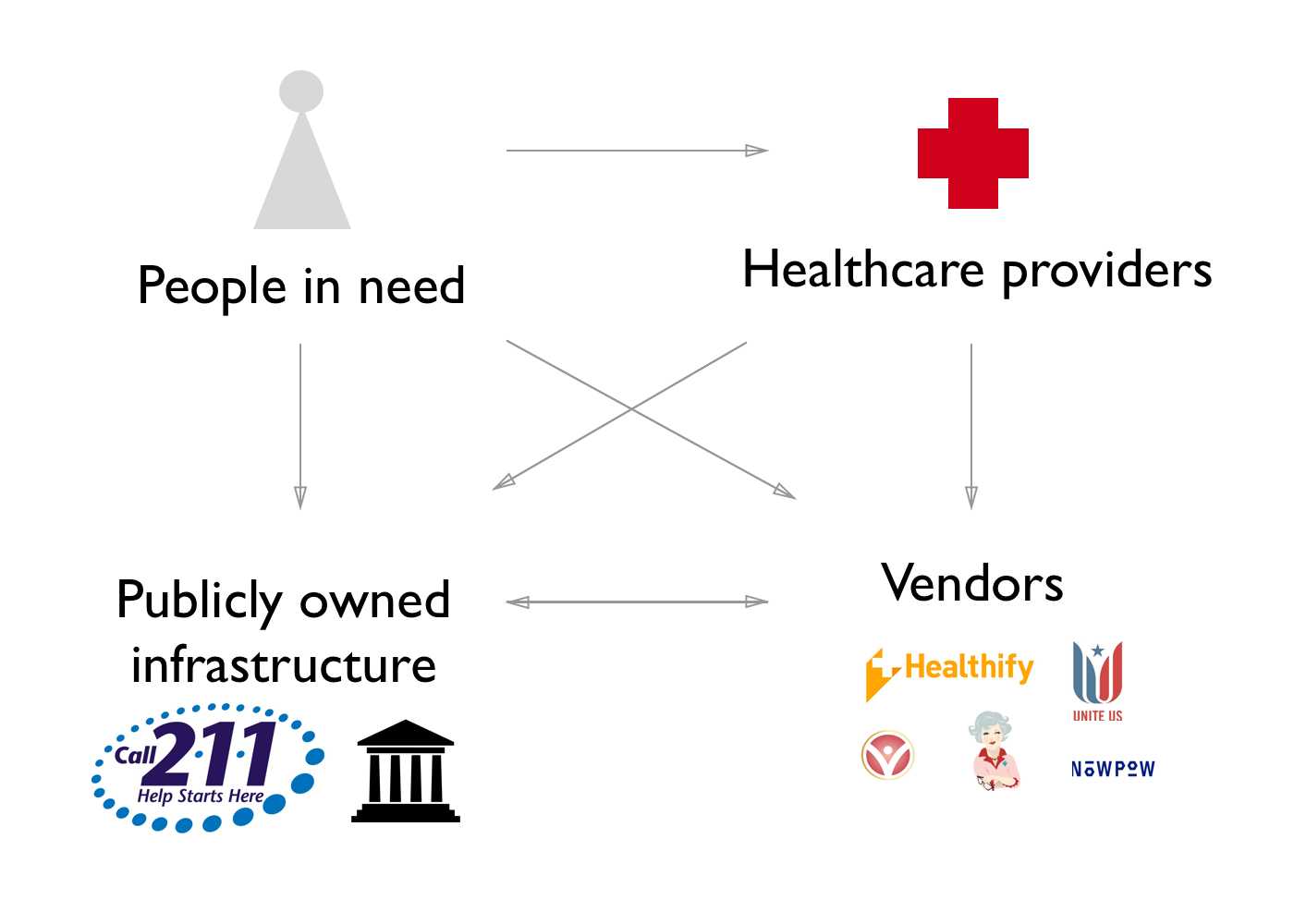

The world we want:

We should have a world where there is robust publicly owned infrastructure that community members and vendors alike can use, participate in, and benefit from. I don’t think the private sector should have a blank slate to using public services for profit; there are business and partnership models that are economical for businesses and ensure that public services are being paid for their business value.

Note: In this diagram, I put a nice icon of a Greek-inspired building – what I’ve been told is the universally recognized symbol for government – next to 2-1-1 to illustrate that, while it isn’t currently, 2-1-1 (or infrastructure like it) should be publicly owned, and publicly owned usually means integrated into government.

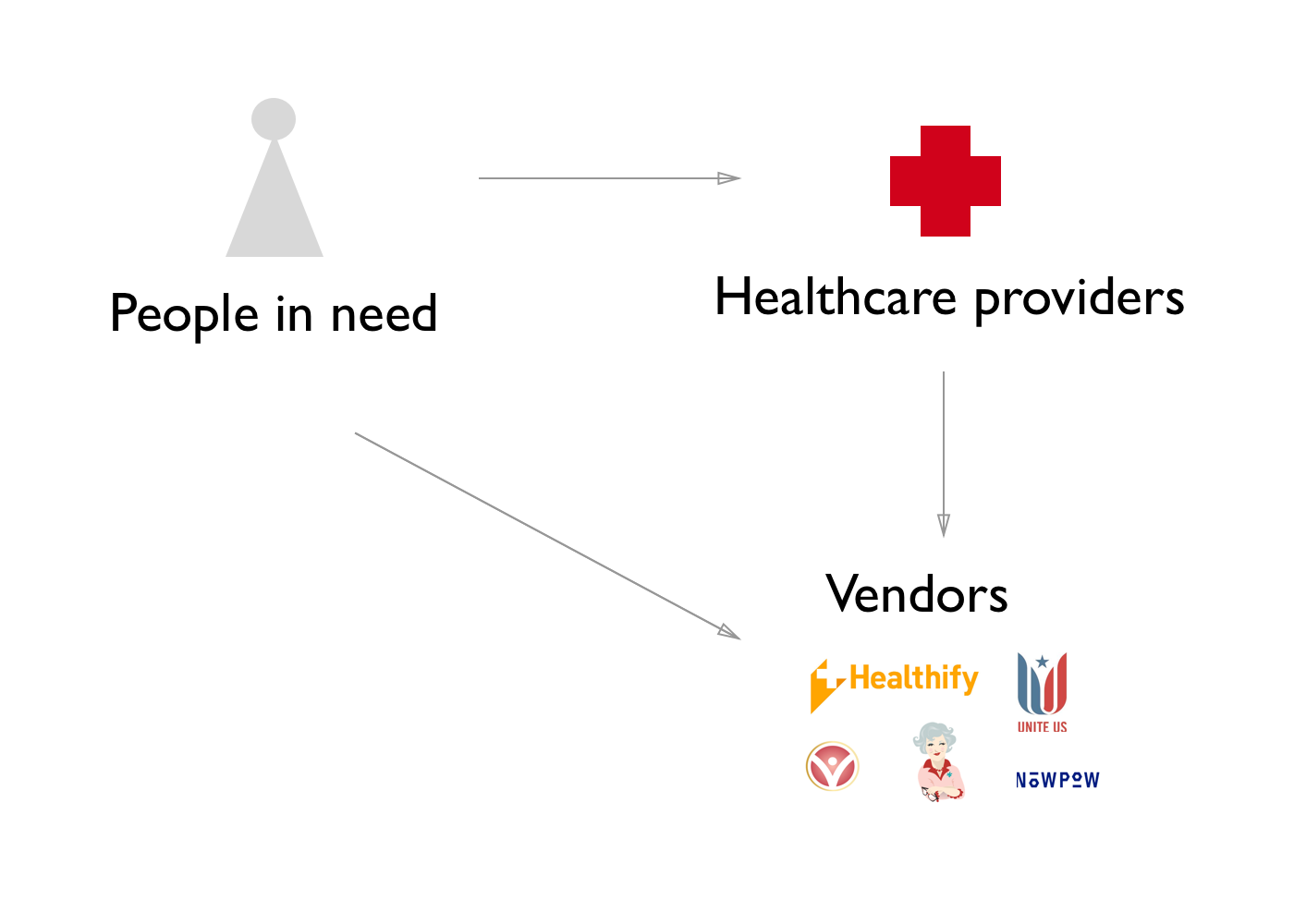

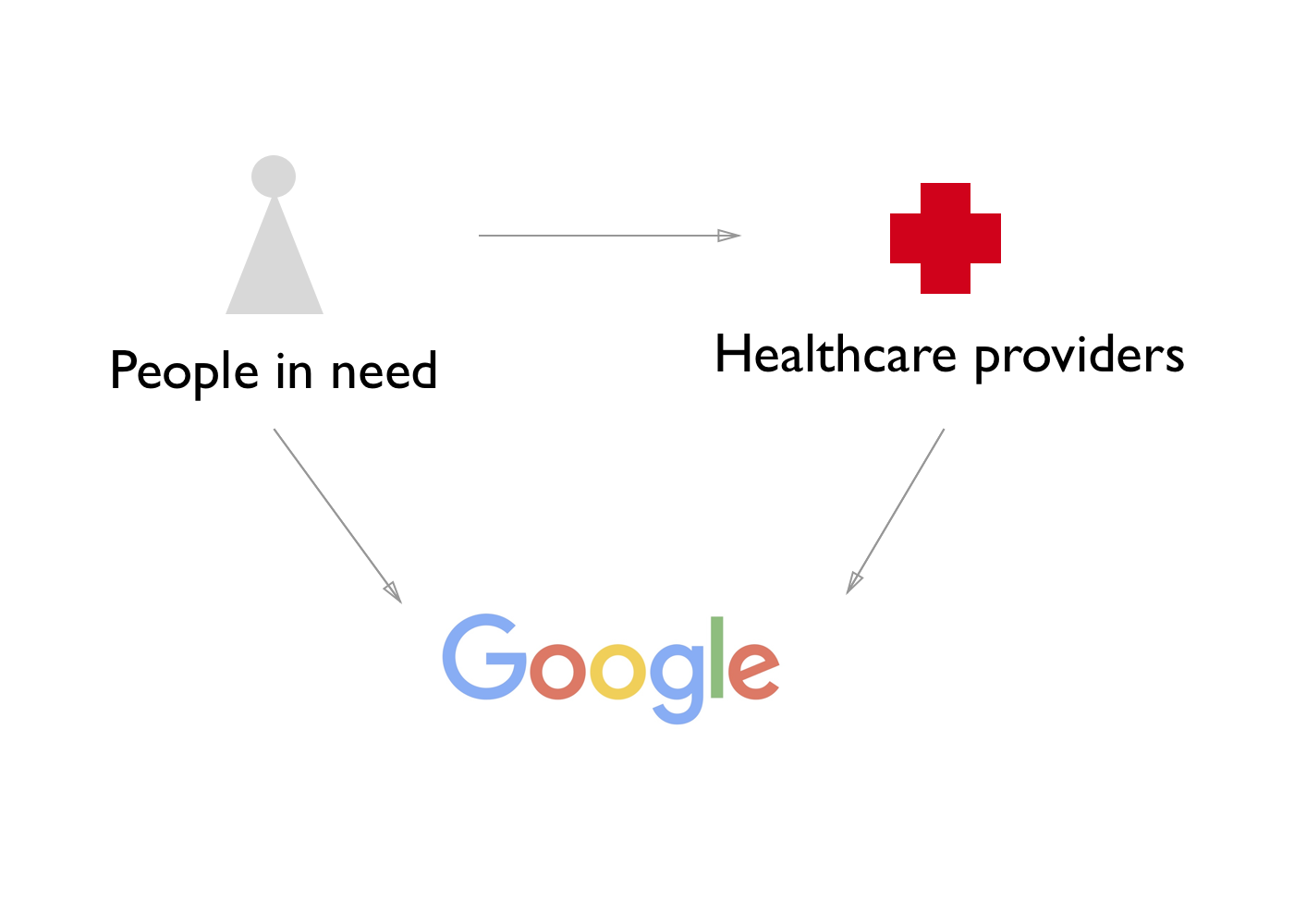

The world we don’t want:

We shouldn’t have a world without publicly owned infrastructure. Without publicly owned infrastructure like this, for-profit companies take on the ethical burden of upholding human rights – and come on, we know they’re not very good at that – and nonprofits have to pick up that mantle without viable motive or means to do so well.

The world we should all be afraid of:

The world we should all be afraid of is one where Google/Alphabet or Amazon or another massive company replaces public infrastructure. For-profit companies are motivated by profit, not public good, and are certainly not motivated to serve all a community’s residents but rather only the ones with dollars, usually at the expense of those worth dollars. Furthermore, when a single for-profit company holds a monopoly on infrastructure, they are more likely to hold a monopoly (or at least a choke-collar) on innovation that uses that infrastructure, unless there is policy enforced to prevent this.8

Getting to the world we want

It starts by agreeing on what services and service infrastructure is necessary to uphold human rights. That itself starts with us agreeing on what human rights are, but luckily in the US we have this thing called the Bill of Rights, and in the world we have this thing called the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We agree on human rights, so let’s focus more energy on figuring out how to uphold them.

Once we’ve done that and identified what services are necessary for human rights, we need to build public infrastructure that the public owns.

Public infrastructure tech

On the technical side, our public infrastructure needs to use open standards for data exchange so tools are easier to build to use public services and underlying data. This increases access and innovation because it enables any actor, public or private or third-sector, to participate and get value out of the data. We also need to empower public service agencies to be digitally literate and maintain good quality levels of service with their infrastructure.

In the social services landscape, Open Referral has been spearheading infrastructure innovation for years, and is increasingly gaining traction. They organize a working group and maintain the open Human Services Data Specification and related API spec.

Open Referral’s innovation isn’t just technical, but also about people and business. They help 2-1-1s and public entities understand and test out business models and the tech that can support them – which leads me to my next point.

Public infrastructure sustainability

A key part of all this is making public infrastructure not only viable but sustainable. To do this, we need to change our approach to public/private partnerships with that focus on building accessible infrastructure, and we need to help the public (and third) sector develop business models of their own to make providing those services to commercial entities sustainable.

Public infrastructure policy

We also need policy to prevent the actors in the private sector from becoming integral yet still profit-driven and privately held pieces of that public infrastructure.9 I’m not saying we need to remove the private sector or profit motives from the equation, but we have to empower the public sector to innovate, to build or buy infrastructure thoughtfully and ethically, and to create partnerships with the private sector that are advantageous for the public, not just the private.