A Model for Participatory Public Digital Infrastructure

Aug 10, 2022

I hear “participatory” being thrown around a lot these days, including by myself. Participatory budgeting. Participatory democracy. Participatory modeling. Participatory development. It’s an idea I wholeheartedly strive for in my own work with governments and communities, with varying degrees of success and frustration. But what does this actually look like, for public digital infrastructure and the policies/programs that technology supports?

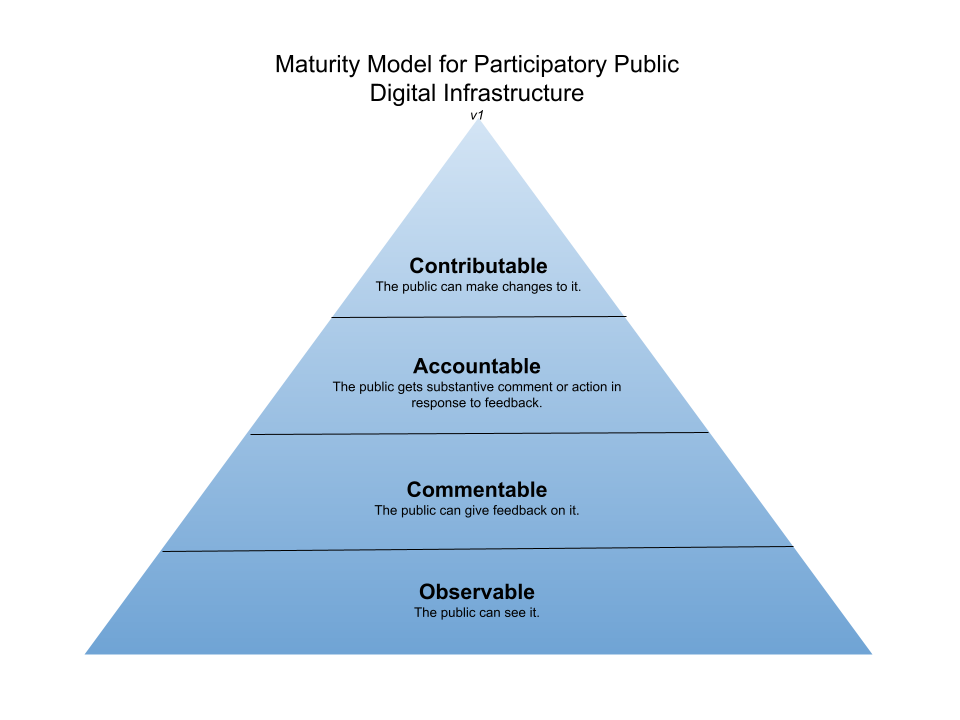

“Participatory” fundamentally means “affording the opportunity for individual participation.”1 I’ll let you dive into the links above for other examples of how to apply “participatory” to important public policy programs, but for tech, I’ve summarized how we can think about levels of participatory engagement in a maturity model, illustrated by this pyramid chart with a deliciously default blue gradient.

Level 1: Observable

As a foundation for any sort of more interesting or more meaningful participatory interaction, your tech has to be observable. That means the public can see it. To be clear, I don’t mean that the public can see and access every system the government makes from a user interface perspective – plenty of systems reasonably require users to create accounts and be authorized for access to data or pages. What I mean is that the code is observable, and it shows what was built and how.

For example, CDC’s PRIME SimpleReport app helps schools and other organizations report COVID tests to the proper authorities. Anybody can’t just open the app and see the live data being entered, BUT anybody can go see how the app was built by looking at its open source code.

Level 2: Commentable

The next level is commentable. This means the public has avenues for giving feedback on the product/tech/system. This could be a survey on the product’s website. It could be the Federal Register.2 It could be an email inbox or a public google group that people join and submit comments to. It could also be a code repository on a social coding platform like Github or GitLab, where the public can create issues (topics for discussion that may correspond to work to be done, such as bug reports or feature requests) and comment on issues or pull requests (a new chunk of code representing a new feature or bug fix, for example, that a contributor has requested to add to the code base that is now going through a review process).

It could also be a combination of some or all of the above, as is with the example of the Caseflow project from the Department of Veterans Affairs. There is a user support system that apparently gets channeled to the tech team, who created an issue on Github reporting the bug and opening discussion round the topic. Arguably, this gets into the next level, but I’m using this to show that you can include comments from other sources, not just your code publishing platform.

Level 3: Accountable

To get to level 3, you have to close the feedback loop and become accountable. Respond to public comments. Be able to point to precise changes that were made from feedback, such as adding a new feature, changing some text to plain language, fixing a bug, etc. If you can’t make the change requested, explain why. Nobody wants to speak into a black box – and nobody will take the time to do so if they don’t have reason to believe it will make a difference.

CMS’s open source Price Transparency Guide offers good examples of accountability using public discussion and linking questions and comments to pull requests representing work being done, such as this discussion, which coincidentally also discusses the (in)feasiability of open sourcing CMS’s 7 million lines of claims code, as well this issue, which links to pull requests addressing the problem.

Level 4: Contributable

Finally, you’ve hit peak participatory maturity when you’re able to and are actively accepting public contributions to your product. This is really the holy grail of participatory tech, and it’s what open source advocates have been dreaming about for decades. It’s incredibly difficult to achieve. To be able to even just accept contributions, you have to have the capacity to educate new contributors about the contribution process and conventions of your project to make sure their contributions are of high quality, and then to review requests to change code, content, or design, working with the contributor through any changes you want to see before you accept their request.

But even if you’re able to accept contributions, that doesn’t mean you will have people clamoring to submit them. A project I’ve helped lead, the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, has been designed for Level 4 since the beginning, but even though we’ve had 75+ individuals attend meetings and participate in discussion at any given time, we’ve had only 4 people outside of the US Digital Service contribute code. We’ve had more people contribute research and analysis, as discussion on Github issues, in our Google Group, and in our ongoing catalog of the environmental justice data landscape – and these contributions are just as valuable as code.

Caveats

This model really only applies to singular products/projects/systems that have already been conceived of; it does not include considerations for a participatory process of originating a digital product/project/system. Multidisciplinary teams of program specialists and tech, product, and design staff should use iterative, human-centered design to work with users (i.e. members of the public) to identify what should be built and what that thing should do. User research, however, is not the same as a participatory process enabling members of a given community to identify what problems should be prioritized – this is more in the vein of participatory development, and worth more exploration later.

This model also doesn’t address the complexity of how to integrate participatory policy with participatory tech. In my experience, this is one of the hardest things to do.

Let’s say you have a system that hosts an algorithm identifying communities that are eligible for a specific grant, for example. If someone from the public can see this code and comment on a part of the algorithm they disagree with, who should respond? The tech product team building the system, or the policy makers deciding what the algorithm does? If someone identifies a bug in the algorithm and submits a fix, but that fix removes 20% of the communities identified, does the tech team decide to accept the fix, or does the policy stakeholder need to approve or reject it first? How is that communicated?

What this indicates is that you can’t separate the tech from the programs or policies it is designed to support, and teams need to be working closely together towards the same outcome goals and with a shared understanding of how participatory engagement should shape the program and its delivery. The example of CMS’s Price Transparency Guide and attempts to codify rules as (open source) code are efforts that directly tackle this bridge, but in many cases we’re still far from it.

Finally, public digital infrastructure can only be as participatory as the public has capacity to participate in it. To achieve real equity and quality in engagement, we have to invest in communities, especially overburdened and underserved ones, to build capacity, tech/data literacy, and policy literacy.